Evening brought the breeze, channelled by the concrete blocks, blowing across Singapore. Evening set the birds chattering, as if desperate for one last word before darkness silenced them. Evening brought light, flooding the corridors of the concrete blocks and lining the roads. The daytime of tinted windows and air-conditioning was giving way to the night-time of flourescent tubes and halogen headlights. White then red flashed from the cars speeding past on the road outside Ah Leong's window.

Across the country, televisions were coming on … Husbands greeted wives and changed channels. Children greeted mothers and clamoured for dinner. Ah Leong stood at the window and looked out, trying to fix all Singapore in his gaze.

In the hazy distance, the skyline of the central business district stood in quiet repose, an august ovation to the country's wealth and prosperity, a singular metaphor for Singapore.

Your eye caught a plane slanting from the southwest, tiny from afar, slowly descending over the scattered islets. Then it turned from round the Marina Bay area, cruised along East Coast park, and disappeared among the thicket of buildings and trees.

It reminded you of being on a plane once, returning from a holiday, and how Singapore looked from above as the plane neared its shores. First the cosy cluster of skyscrapers appear, gleaming in the late afternoon light; then the neat landscape of trees, fronted by new condominiums and repainted HDB flats; and then the red-roofed terrace houses of Tanah Merah, the neat white boxes of Changi Business Park, each view the gentle turning of a page, before you landed on the tarmac. Changi Airport. You felt a rising pride. Singapore was already resplendent in your mind, and Singapore was not just Singapore. It was the garden city, it was the oasis in Southeast Asia, a buzzing metropolis, a city of possibilities, it was the legion epithets from the saga of modernity, Singapore as knight examplar, and you, citizen, were the custodian of her lustrous honour.

But what was Singapore really like, as seen on the ground, beneath the sleek taglines dreamt up by the Tourism Board, behind the daily spiel from its contemptible, state-controlled media, beyond its inebriated and indoctrinated citizenry from amidst its shopping malls and skyscrapers? What was Singapore really like, as lived?

'Welcome home,' the demure Singapore Girl exuded through the announcement.

The passenger beside you turned around, and said, 'Doesn't Singapore look like a wonderful Legoland?'

Yes, you said.. 'Wonderland. Unreal City.'

* * *

There was a time when Singapore appeared indubitable to you, almost paradisal. Everything worked, you were told. Worked like indefatigable clockwork. Everyone was housed, everyone received an education, everyone carved out a career. It was the life; the life to have, and the life to live. You saw it for yourself. You lived it; you lived it up. And so did everyone else. Little did you know, it was only a life to live and dream the permitted dreams. That time was like a previous life now.

Once, while you were still living in that previous time and its prescribed dreams, you were walking through a lunch hour crowd, and a voice thundered out from nowhere. You turned to that voice, and caught an elderly man with unusual sideburns, gazing at the flowing throng. He had on his face an absorbing expression, and he was holding on to a book.

'Make it right! Make it right for Singapore!'

It was that thunder again. It was as if he was declaring independence..

You paused for a moment, standing a few steps away, taking him in. You were curious. There was nothing wrong with Singapore, you thought. Everything was right in their places.

You looked around at the passing crowd, crisp shirts, shopping bags, after lunch, and all of them seemed to agree with you. Life was right. They ignored him. You felt vindicated.

Was that man a lunatic?

You were curious about why that man was there, standing like a stubborn sunset against another burning sun. What was it he saw in Singapore that was wrong, that had to be made right? But you were afraid of approaching him. You did not know why you were afraid. You just were. So instead of plucking his story off his waving hand for a few dollars, you went away and got his story off other people's mouths and through another's eyes.

He was a London-educated lawyer, a former magistrate, and an opposition member of parliament – the first one. He spoke against the government. He was sued for defamation, and he was made a bankrupt. He lost his silk and his robes. Now he was a lone figure beneath this gleaming city, peddling his stories.

You wanted to know what that man had done, who had risen so high only to have been reduced to this ground. The readings that you had gathered revealed little and gave no real answers. So you cast wider your search, for materials not available easily, for perspectives not presented in the mainstream channels, for books the local bookshops did not stock. You wondered why they were not easily found.

As you read on, another story of your country beckoned, another Singapore, one that was seen through that fiery man's eyes. It was the Singapore that you had not noticed, or felt was inconsequential, or did not care much for and thus abstracted and erased from your mind.. You do that to images that either disturbed or that you did not comprehend – ignoring them was easier on the eye, and they would be absent from your mind. It made life look rosier. As you read on you felt an awakening that gradually obliterated the glittering Singapore that you thought you had always known, the white-washed Singapore.

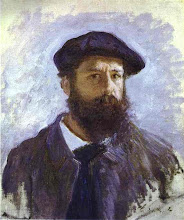

Put together, it was a fuller painting of your country, blemished, imperfect, but one that was more authentic, and one that had heart and character, like that masterpiece of oil on canvas, bravely true to its faults and thus so precious, rather than an amateur's attempt at perfect reproduction, barely true, and merely producing pastiche.

And you thought how ignorant you otherwise must have been, how one-dimensional, how shallow.. And how easy, to half-asleep through your life that only lives and dreams the permitted dreams.

* * *

There was also a personal story of that man, his story, intricately intertwined with the myriad recent histories of your country. It was one of courage and of conviction, told from another side, but that was seldom heard.

You thought very few Singaporeans came near this man's achievements. Even fewer who had that kind of courage and convictions. He understood and meant every word of Majulah Singapura. He recited the Pledge not as a pledge of dependence; not as emptiness or distraction. He dared live out his convictions in a country that convicted those beliefs. He resolutely countenanced not only the powerful, but also the powerless and the weak, who had viewed him either with disdain, or dared not look him in his eye, though his irises never lost that gleam like a child's.

Why was there no place here for someone like that man,

you wondered. Someone who had courage, convictions, and humanity, flowers so rare in this country. Was it right for convictions to come head on with the white night of power, only to wither and lose, everything and all, and for what reason?

Truth, justice, and liberty; grand words but for whom?

That man could have lived the high life of the state, amongst the legal fraternity and high society. But he did not, for that would have compelled him to close an eye, to bury his beliefs, and to forget one's heart. So he left that lofty circle to be amongst ordinary citizens like you, who could only dream of attaining a flake of what he once upon a time had, in riches and in poverty. Where he could have earned millions, you made him pay millions, because he dared to speak up for you, when you were wavering in hesitation and in fear. Because he was willing to give up all that most of you would never have, not with all the dreams in the world.

When this man died, his name was whiter than white, a colour above those draped always in white. He had no slush funds, no secret bank accounts; how to, when he had nowhere and no wish to hide? Decades of ruthless hounding and smearing, and not bone in his closet, not a stain on his clothes. And you wondered how many among the cloistered powerful in Singapore could hold on to as pristine a flake as his.

Why were they so afraid of him, and what were they afraid of?

This great man died of heart failure. But was it only his heart that had failed him?

* * *

Across the sky, it was almost pitch dark now, except for the Singapore below you, all ablaze with lights, presenting this luminous tapestry on the horizontal, hanging a different view of Singapore.

This country could indeed appear different if only you would contemplate it with your own eyes – your own – and under a different light.

You thought of that man and his lone voice, a pure plume of sound, rising quick above the diffident crowd, 'Make it right! Make it right for Singapore!' And you remembered that you would not have had this other glimpse of the Singapore that you now see, that had been kept away from you, by others as well as by yourself, had you not paused for just a moment that afternoon in the city, and pondered about that man's words, and about the Singapore that you smugly thought you had always known.

Still standing on your reverie by the window, your recollecting gaze kindled one more memory, one that told the story of how you came to pause moments, of pausing moments stopping time, and how, like magic carpets and gems of literature, they could take you to another world.

You were thirteen, a teenager, you were finding yourself a stranger in this world, alone, very afraid, and you were trying to find your own secret hiding place. It was the school library, the perfect place for pausing moments, and getting lost in your own searching world. One time, your running fingers along the bookshelves stopped you at a slim novel, First Loves. It was a story about Ah Leong, a Singaporean teenager, just like you, written by a certain Philip Jeyaretnam. As you read it, you felt connected to Ah Leong, his adventures and his feelings, and you laughed at all those vivid thoughts of his, because you knew where he was coming from. The two of you grew up in the same place. You knew all about the sunset that he saw. It was the sun of your own land.

The things you read once upon a time often come to rest at a certain corner in your mind, not as forgotten relics or aimless dust, but as returning motifs of particular images and specific sensibilities, that unbeknownst to you, had palpated your base emotions, guided your thoughts, and influenced your self.. Reading a novel about your own country, written by your fellowman, you discovered through crafted words and local language, through the familiar scenes and remembered corners, a more authentic, and a more enduring soul of the place, the place you that would like to call home, with a sunlight that only you would know. Even as the ground beneath you shifted, the places transformed, or even disappear, there was always a pellucid Singapore in your memory to home in to, across time, wherever you were, however far, however Singapore changed.

As you grew up, there were many times that you walked home in those rusted evenings and remembered Ah Leong, standing there by his window as the evening brought breeze, as he tried to fix all Singapore in his gaze. In a way, he was like your older brother heading first where later you would go: finishing school, falling in love, landing your first job, having your first kiss; all the familiar moments of Singapore that you had duly lived, and always that homely colour of evening.

In a way, you were Ah Leong, already written into a story without your knowing.

Without your knowing; has it been so long ago, when you had first read a book that spoke to you, heart to heart, and told you a story about home, reviving your childhood memories and conjuring your future time, all from a single opening line: The evening brought breeze, channelled by the concrete blocks, blowing across Singapore …

And you were thankful for that second of serendipity, for thereon, your evenings had often brought along with them, those precious reflections of light; those that bided time, dappled your conscience, and led you to see and imagine a different, a truer, and a more heartfelt Singapore. Those that led you to ponder a moment the words of that lone man, all fire and all heart, hidden in the chary crowd, in the sun of your own land, pure voice above them all.

*

Kindly support the JBJ Scholarship Fund for Postgraduate Study in Law and Human Rights.

For more information, please contact: Mr Kenneth Jeyaretnam (kjeyaretnam@gmail.com)